HTTP/2 multiplexing bundles many requests over a single connection and removes blockages at the protocol level. However, in real networks, TCP head-of-line, TLS overhead, and poor prioritization slow things down, so HTTP/2 does not automatically run faster than HTTP/1.1.

Key points

- Multiplexing Parallelizes many requests over a single TCP connection.

- TCP-HoL remains in place and stops all streams in the event of losses.

- TLS setup can significantly delay time-to-first-byte.

- Priorities and server push only work with clean tuning.

- page type decides: many small files vs. few large files.

How HTTP/2 multiplexing works internally

I break down each answer into small frames, number them, and assign them to logical streams so that multiple resources run simultaneously over a single connection. This avoids blockages at the HTTP level because no request has to wait for another to finish. Browsers send HTML, CSS, JS, images, and fonts in parallel, reducing the cost of additional connections. HPACK shrinks headers, which significantly reduces the load for many small files. However, the key point remains: all streams share the same TCP line, which creates advantages but also generates new dependencies. This architecture delivers speed as long as the network remains stable and the Prioritization works effectively.

HTTP/1.1 vs. HTTP/2: Key differences

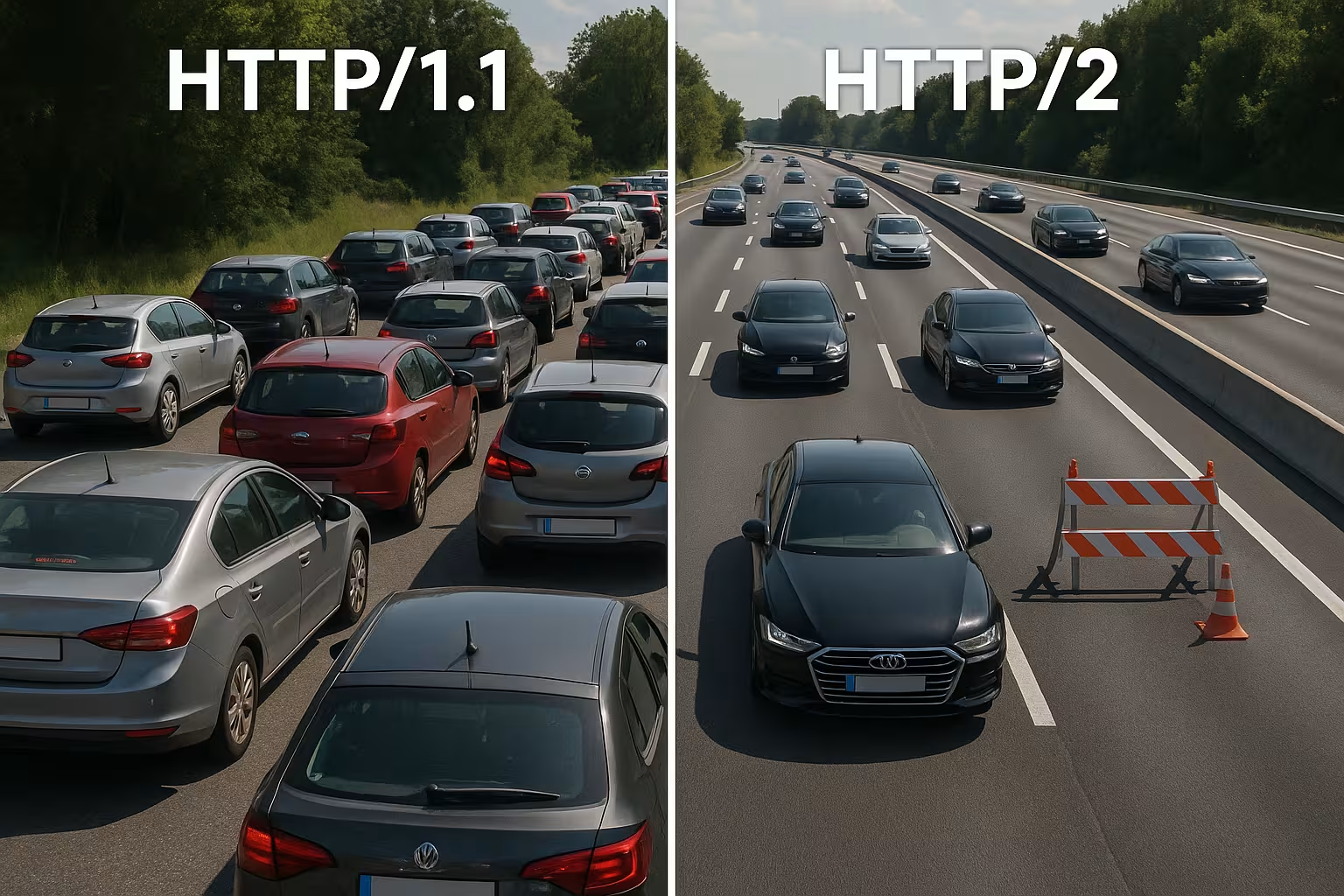

HTTP/1.1 relies on text-based messages and multiple parallel connections per host to load resources simultaneously, which increases handshakes and overhead. HTTP/2 works in binary, uses a single connection for everything, and compresses headers, which reduces waiting times, especially when there are many objects. Long queues disappear in waterfall diagrams because streams progress in parallel. However, the bottleneck shifts from the HTTP layer to the TCP layer, which I notice significantly in unstable networks. Small, heavily cached pages often show little advantage over 1.1, while large, asset-rich pages benefit more visibly. These differences shape my tuning strategy and justify a project-specific decision.

Choosing the right flow control and window sizes

HTTP/2 provides its own flow control per stream and per connection. I pay attention to sensible values for INITIAL_WINDOW_SIZE and the number of simultaneous streams so that the line is neither congested nor underutilized. Windows that are too small generate an unnecessary number of WINDOW_UPDATEframes and throttle the data rate; windows that are too large can overwhelm weaker clients. In networks with a high bandwidth-delay product (BDP), I increase the window size specifically so that large responses do not get stuck in stop-and-go traffic. At the same time, I limit MAX_CONCURRENT_STREAMS Pragmatic: enough parallelism for render-critical tasks, but not so much that minor details slow down the LCP image. These adjustments are small, but they have a big impact on actual loading times when they are tailored to the page and the network.

Reevaluate domain sharding and bundling

Many 1.1 optimizations are counterproductive under HTTP/2. I'm doing away with old domain sharding because a single, well-used connection is more efficient than artificially distributed sockets. I also question the practice of bundling JavaScript into mega files: smaller, logically separate bundles allow for targeted caches and avoid having to retransmit the entire app when a change is made. Image sprites are becoming less important because parallel requests have become cheap and modern image formats, including caching, are more effective. So I unbundle where multiplexing can win and only bundle when it really simplifies the architecture or measurably increases the caching hit rate.

Connection coalescing and certificates

HTTP/2 allows browsers to use one connection for multiple hostnames if the certificates and DNS match. I plan SAN entries and SNI so that coalescing is possible and additional handshakes are not necessary. If ALPN and cipher suites match, the client can use CSS from cdn.example.com and pictures of static.example.com via the same connection. This saves RTTs, simplifies prioritization, and increases the chance that critical assets will arrive without detours. I check these effects specifically in the Network tab: Is only one socket really being used, or are certificate limits and policies forcing the browser to establish new connections?

Why multiplexing is slowed down: TCP head-of-line

If a packet is lost on the single TCP connection, the entire line waits until the retransmission arrives—this temporarily stops all HTTP/2 streams. In mobile networks with fluctuating latency and increased loss rates, I therefore regularly see lower gains or even disadvantages compared to multiple 1.1 connections. This effect explains why multiplexing looks great on paper but doesn't always work in practice. Measurements from research and field tests show exactly this correlation in real networks [6]. I therefore plan deployments conservatively, test on typical user paths, and check the effects for each target group. Ignoring TCP HoL is a waste Performance and can even increase loading times.

TLS handshake, TTFB, and page type

HTTP/2 runs almost exclusively over TLS on the web, which generates additional handshakes and can significantly increase the time-to-first-byte for a small number of assets. If I only deliver one large file, the multiplexing advantage disappears because no parallel transmission is necessary. Pages with ten to twenty small files tend to benefit more, while single-asset responses are often on par with HTTP/1.1. I reduce overhead with TLS 1.3, session resumption, and clean keep-alive so that reconnections are no longer necessary and the connection really stays alive. For fine-tuning, I rely on Keep-Alive Tuning, to set reuse, idle timeouts, and limits appropriate for the load. This reduces the handshake ratio and the TTFB stabilizes even during traffic peaks.

CDN and proxy chains: h2 to the origin

Many stacks terminate TLS at the edge and continue communicating with the origin. I check whether HTTP/2 is also used between the CDN and the backend or whether there is a fallback to HTTP/1.1. Buffering proxies can partially negate advantages (header compression, prioritization) if they reserialize responses or reorder sequences. I therefore optimize end-to-end: Edge node, intermediate proxy, and origin should understand h2, run appropriate window sizes, and not ignore priorities. Where h2c (HTTP/2 without TLS in the internal network) makes sense, I test whether it saves latency and CPU without violating security policies. Only a coherent chain unfolds the Multiplexingeffect completely.

Using prioritization correctly

I prioritize critical resources so that HTML, CSS, and the LCP image arrive first and render-blocking issues are eliminated. Without clear priorities, less important scripts consume valuable bandwidth while above-the-fold content waits. Not every server correctly observes browser priorities, and some proxies change the order, which is why I evaluate results data rather than wishful thinking [8]. Preload headers and an early image reference shorten load paths and increase the cache hit rate. Prioritization doesn't work magic, but it directs the one connection so that users quickly see what they need. Clean rules bring noticeable Thrust and make multiplexing truly effective.

Prioritization in practice: Extensible Priorities

Browsers have further developed their prioritization models. I take into account that modern clients often use „extensible priorities“ instead of rigid tree weights. They signal urgency and progressive parameters per stream, which servers must interpret and translate into fair schedulers. I check whether my server respects these signals or is based on old behavior. In A/B tests, I compare loading paths with and without server-side prioritization to identify displacement effects. Important: Prioritization should favor render-critical content, but must not lead to starvation of long-running downloads. A careful mix avoids peaks and keeps the pipeline free for visible content.

Server Push: rarely the abbreviation

I only use server push selectively because over-pushing takes up bandwidth and ignores browser caches. If a resource that has already been cached is pushed, the path slows down instead of speeding up. Many teams have disabled push again and are much more reliable with preload [8]. In special cases, such as on recurring routes with clear patterns, push can be useful, but I prove the effect with measurements. Without evidence, I remove push and keep the pipeline free for data that is really needed. Less is often more here. more, especially on the only connection.

Practical comparison: When HTTP/1.1 can be faster

I find HTTP/1.1 to be competitive when a few large files dominate or networks with higher losses are used. Multiple separate connections then spread the risk and can shorten individual first byte times. On very small pages, additional TLS handshakes often completely offset the multiplexing benefits. With many small objects, however, HTTP/2 comes out on top because compression, prioritization, and a single socket are effective. The following overview shows typical patterns from audits and field tests that guide my choice of protocol [6][8]. This grid does not replace testing, but it does provide a solid Orientation for initial decisions.

| Scenario | Better protocol | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Many small assets (CSS/JS/images/fonts) | HTTP/2 | Multiplexing and HPACK reduce overhead; one connection is sufficient |

| Few, very large files | HTTP/1.1 ≈ HTTP/2 | Hardly any parallelism required; handshake costs outweigh other factors |

| Unstable mobile networks with losses | HTTP/1.1 partly better | TCP-HoL stops all streams with HTTP/2; multiple sockets can help |

| Optimized TLS (1.3, resumption), clean priorities | HTTP/2 | Lower setup, targeted bandwidth control |

| Over-pushing active | HTTP/1.1/HTTP/2 without push | Unnecessary data clogs up the line; preloading is safer |

Best practices for real loading time gains

I reduce bytes before the protocol: images in WebP/AVIF, appropriate sizes, economical scripts, and clean caching headers. I keep critical CSS path parts small, load fonts early, and set fallbacks to avoid layout shifts. For connection establishment and DNS, I use Preconnect and DNS Prefetch, so that handshakes start before the parser encounters the resource. Brotli for text content speeds up recurring requests, especially via CDNs. I check effects in the waterfall and compare LCP, FID, and TTFB before and after changes. Measurements guide my Priorities, gut feeling doesn't.

gRPC, SSE, and streaming cases

HTTP/2 really shows its strengths with gRPC and other bidirectional or long-running streams. I pay attention to timeouts, buffer sizes, and backlog rules to ensure that a stalled stream does not disadvantage all other requests. For server-sent events and live feeds, a stable, persistent connection is helpful as long as the server manages priorities correctly and keep-alive limits do not take effect too early. At the same time, I test how error cases behave: Stream reconstruction, exponential backoff, and sensible limits for reconnects prevent load spikes when many clients disconnect and reconnect at the same time. This keeps real-time scenarios predictable.

OS and TCP tuning for stable multiplexing performance

Protocol selection does not compensate for a weak network configuration. I check congestion control algorithms (e.g., BBR vs. CUBIC), socket buffers, TCP Fast Open policies, and the initial congestion window size. Congestion control that is appropriate for the path can reduce retransmissions and mitigate HoL effects. Equally important: correct MTU/MSS values to prevent fragmentation and avoidable losses. At the TLS level, I prefer short certificate chains, OCSP stapling, and ECDSA certificates because they speed up the handshake. Taken together, these settings give multiplexing the necessary Substructure, so that prioritization and header compression can take effect.

Measurement strategy and KPIs in everyday life

I don't rely on median values, but look at p75/p95 of the metrics, separated by device, network type, and location. Synthetic tests provide reproducible baseline values, while real-user monitoring shows the dispersion in the field. I compare waterfalls of key paths, check early bytes of HTML, the order of CSS/JS, and the arrival time of the LCP image. I roll out changes as controlled experiments and observe TTFB, LCP, and error rates in parallel. Important: I remove any prioritization that has no measurable benefit. This keeps the configuration lean and allows me to invest in adjustments that are statistically proven to save time.

Crawl and bot traffic

In addition to users, crawlers also benefit from clean HTTP/2. I activate h2 for relevant endpoints and observe whether bots reuse the connection and retrieve more pages in the same amount of time. Unnecessary 301 cascades, uncompressed responses, or keep-alive limits that are too short cost crawl budget. I coordinate policies so that multiplexing also works here without exceeding backend limits. The result: more efficient scans and greater stability under load.

HTTP/2, HTTP/3, and what comes next

HTTP/3 relies on QUIC over UDP and resolves TCP head-of-line blocking, which is particularly helpful in terms of mobility and losses [6]. Connection establishment is shorter, and stream blockages no longer affect all requests simultaneously. HTTP/2 remains important in mixed fleets, but I enable HTTP/3 where clients and CDNs already speak it. Detailed comparisons such as HTTP/3 vs. HTTP/2 help me plan rollouts in phases and tailored to specific target groups. I measure separately by location, device, and network type so that real users benefit. This way, I use protocols to Loading times in everyday situations.

Hosting and infrastructure as accelerators

Good protocols cannot save weak infrastructure, which is why I carefully check the location, peering, CPU, RAM, and I/O limits. A modern web server, reasonable worker numbers, and a cache layer prevent the only connection from ending up in a bottleneck. Strategic CDN use shortens RTT and cushions peak loads. Those who serve users across Europe often benefit more from short distances than from protocol fine-tuning. I plan capacity with reserves so that burst traffic doesn't bring things to a standstill. This is how multiplexing unfolds its Potential reliable.

Recognize error patterns quickly

If HTTP/2 seems slower than expected, I look for typical patterns: a single long transfer blocking many small ones; priorities being ignored; high retransmission rates on mobile connections; or TLS resumption not working. I then compare HTTP/2 and HTTP/1.1 under identical conditions, separate CDN influence from the origin, and look at the number of sockets, the actual number of streams, and the order of the first kilobytes. If I find a bottleneck, I first adjust the basics (bytes, caching, handshakes) before tweaking flow control or priorities. This sequence delivers the most reliable improvements.

Practical summary for quick decisions

I use HTTP/2 multiplexing when there are many objects, priorities apply, and TLS is configured correctly. With few large files or unstable networks, I factor in minor advantages and keep an eye on 1.1 results. I only use server push with evidence, preload almost always, and I keep overhead low through compression, caching, and early connections. Measurements with real devices and locations confirm my assumptions before I roll out changes broadly [6][8]. In the end, it's not the protocol number that counts, but noticeable speed for real users. If you proceed this way, you can reliably get the most out of HTTP/2. Speed and lays the foundation for HTTP/3.